From: Whales in the Classroom – Oceanography

By Lawrence Wade

Graphics by Stephen Bolles

Oceanography Lesson 5 – Marine Communities

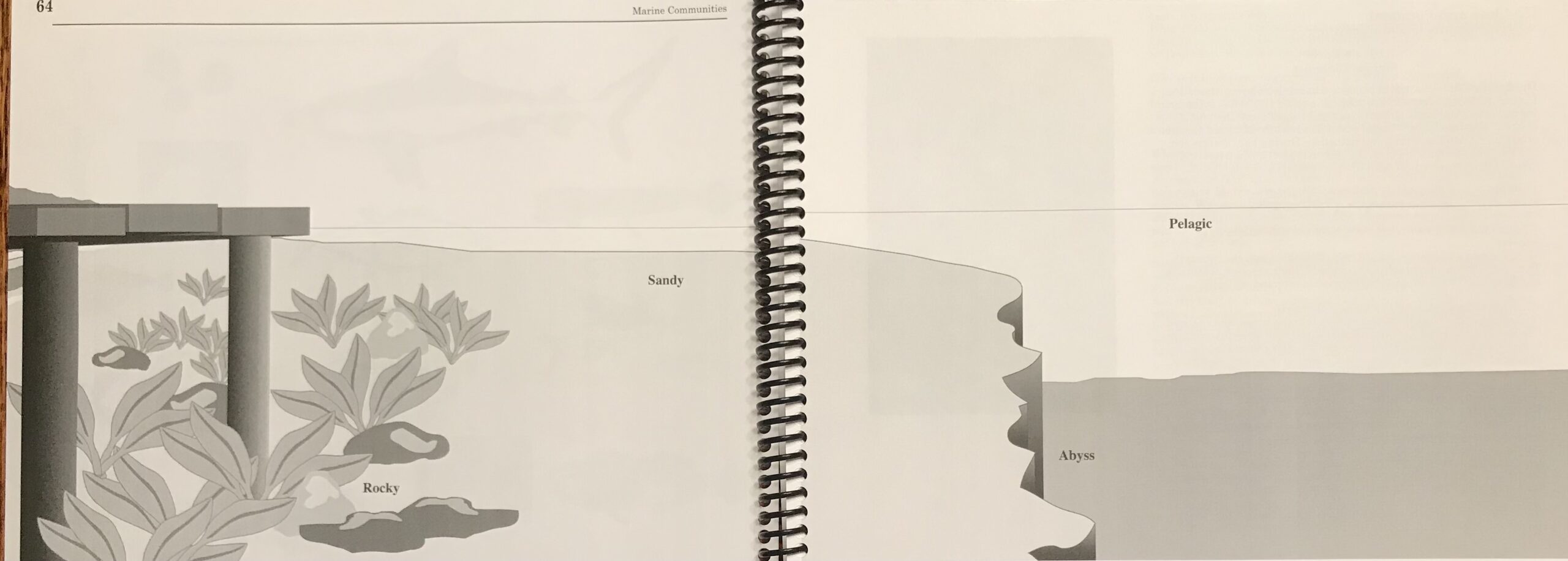

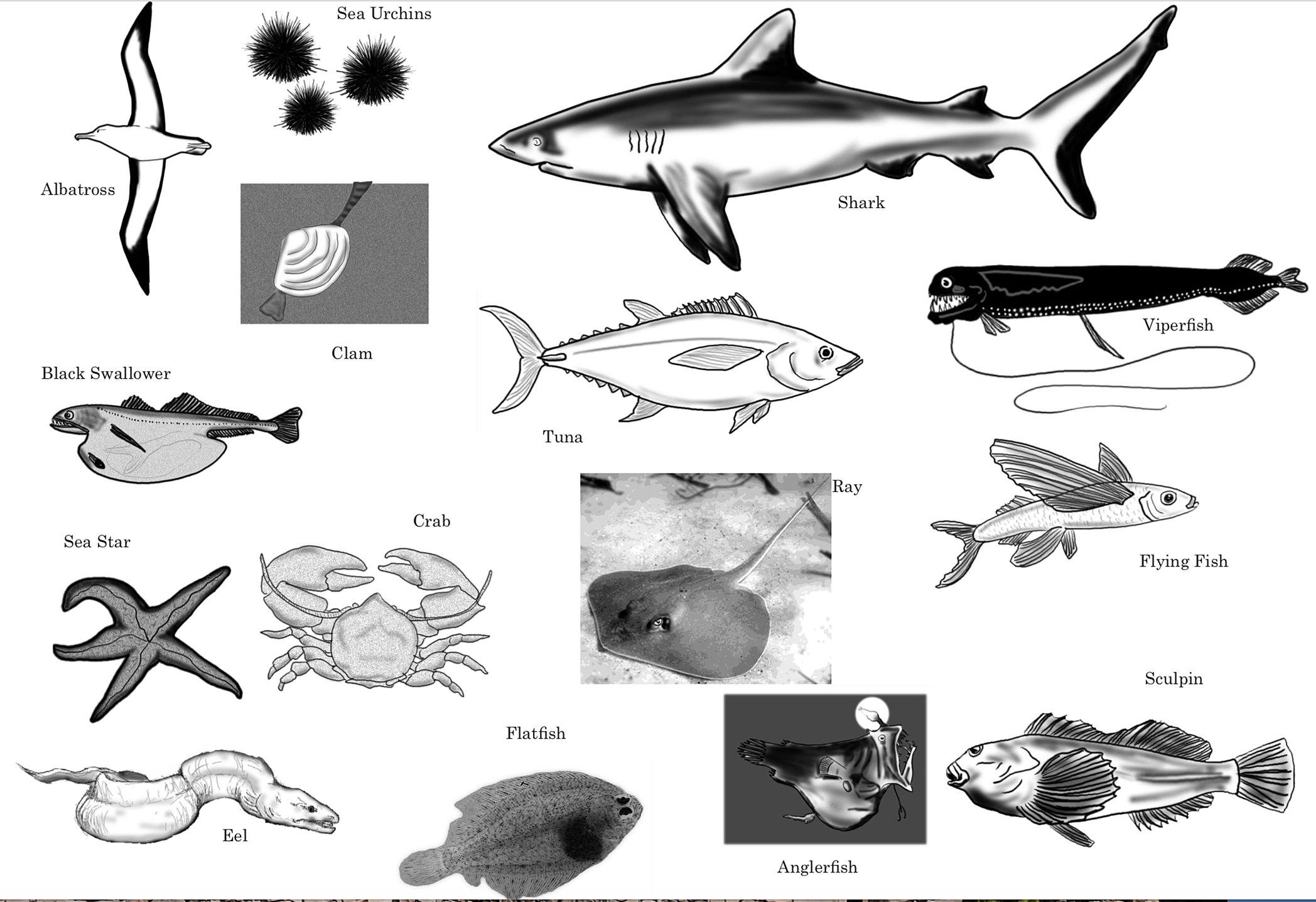

The ocean has diverse communities within it. These communities are unique places that have creatures only found in those areas. For instance, the rocky shore community has a unique set of creatures specialized for living in a rocky environment. We will be exploring other communities including the sandy beach community, pelagic ocean, and the deep sea abyss. Each one of these communities has special characteristics that are as unique as the animals that live there. The animals that inhabit the community may only be found in that area.

The ocean has diverse communities within it. These communities are unique places that have creatures only found in those areas. For instance, the rocky shore community has a unique set of creatures specialized for living in a rocky environment. We will be exploring other communities including the sandy beach community, pelagic ocean, and the deep sea abyss. Each one of these communities has special characteristics that are as unique as the animals that live there. The animals that inhabit the community may only be found in that area.

We will also be learning about animal adaptations. An adaptation allows an animal to survive in a particular place. For instance, the bodies of animals that live in the sandy beach community are specialized to allow them to survive in that community.

The Sandy Beach Community

The sandy beach community is on the continental shelf where water is less than 400 feet deep. The area is flat and sandy in all directions. There are no plants and not much visible life. The creatures who live in this area must figure out a way to hide on the bottom or in the sand. Many of the creatures who live in this community are flattened and lay on the sand or burrow into it.

Critters Found in Sandy Areas

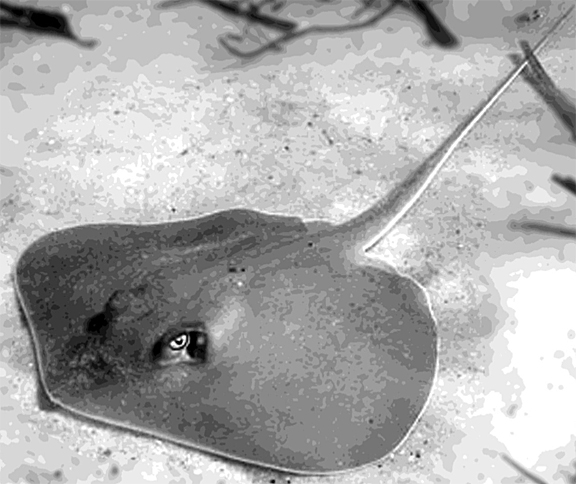

Ray

Rays are close relatives of sharks. Their large wings (up to 10 feet in length) are actually pectoral fins, which they use for swimming. Rays are found in shallow sandy or muddy bottoms where they feed on clams and crabs. Rays flap their wing-like fins close to the bottom to expose buried clams. They also use their wings to help bury themselves in the sand. Only the sting rays are harmful to humans since they have a poisonous stinger at the base of their tail. The stinger is 2–3 inches in length and knife-like in shape. Sting rays are not aggressive, but people have been hurt when they accidentally stepped on the back of a ray buried in the shallow sandy water.

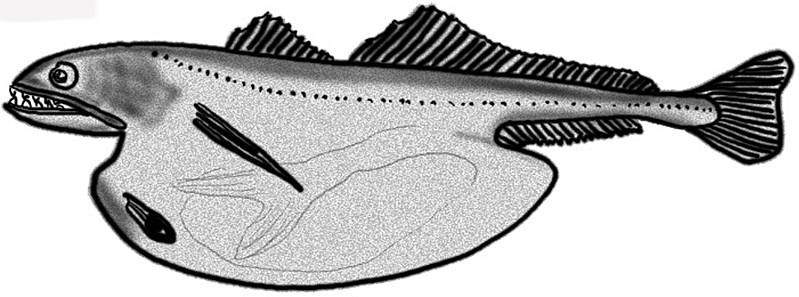

Flatfish

The flatfish also is well adapted to life on the bottom. As an adult, its body is flattened like a pancake, with both eyes on one side of its head. Its flattened body allows the fish to easily cover itself with sand. It swims on its side, moving its tail up and down in the same manner as a whale. However, as a fry (newly hatched fish) it looks more like a normal fish. It lives near the surface, swims upright, moves its tail from side to side (like most fish), and has one eye on each side of its head. When the young flatfish grows to one inch long, it begins to transform into the adult. The eyes shift to one side of its head and it begins swimming on its side and living on the bot- tom. Clam

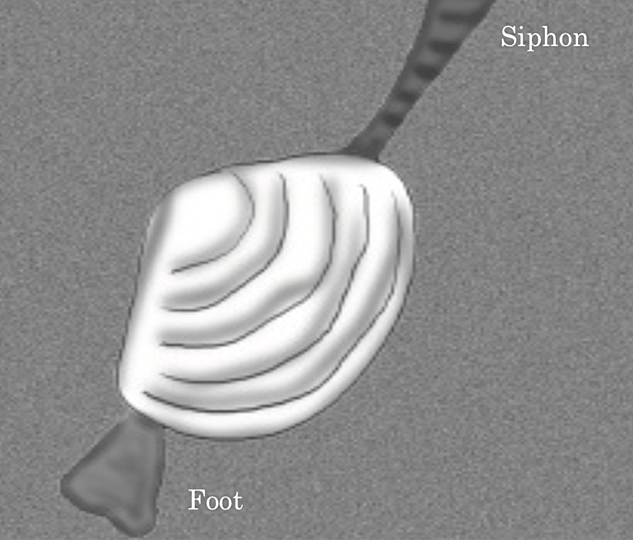

Clam

Clams live beneath the ocean floor in sand up to 3 feet deep. Two shells surround the body of the clam for protection. Clams have a siphon tube which they put above the surface of the sand. This siphon is used to filter microscopic plankton for food and to take oxygen from the water. Clams have a muscle called a “foot” that helps them burrow into the sand. This “foot” expands and contracts to push the clam through the sand.

The Rocky Shore Community

The rocky shore community is on the continental shelf where the depth is less than 400 feet. Being in the rocky shore is sort of like being in the woods on a dark windy night. There are seaweeds swaying back and forth and there are many types of fish darting through the weeds. There are a lot of boulders, holes and cliffs which provide homes for many animals. Many of the fish that live in this community have thin bodies to allow them to fit into holes. Many of the invertebrates (animals without backbones) are adapted to holding onto rocks in various ways.

Critters Found in Rocky Areas

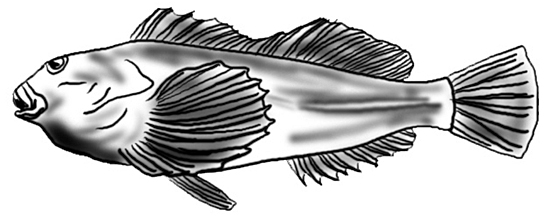

Sculpin

Sculpins are thin-bodied fish with large heads. The thin body allows sculpins to explore holes. They have large pectoral fins that help them to turn in tight places. Sculpins are slow, bottom-dwelling fish that feed primarily on crabs, snails, and small fish. The eggs are laid in a nest and are guarded by the parents until hatching. Although the adult sculpins live close to shore, the young may be found in the offshore plankton over 200 miles from land.

Eel

Eels have long snake-like bodies (up to 10 feet in length) that allow them to pursue their prey and to hide in small holes. They make their homes in dark holes, and feed mostly at night. They have long needle-like teeth to help them grab and hold fish. Moray eels will attack humans if they are wounded or disturbed.

Sea Urchin

The sea urchin is a bottom-dwelling animal with long spines covering its body. The spines protect the slow-moving urchin from predators. The spines are not poisonous, but a spine lodged into a human foot or hand is difficult to remove and is likely to cause a nasty infection.

The sea urchin is a bottom-dwelling animal with long spines covering its body. The spines protect the slow-moving urchin from predators. The spines are not poisonous, but a spine lodged into a human foot or hand is difficult to remove and is likely to cause a nasty infection.

The sea urchin scrapes algae and seaweed off the rocks with its five teeth, which are joined together in a cone shape on its underside. If there are not enough predators (sea star, wolf eel and sea otter) to keep sea urchin populations under control, then urchins can devastate entire kelp forests and other seaweeds.

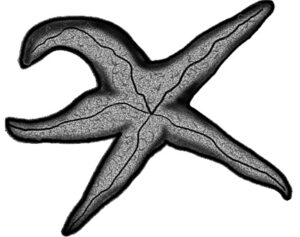

Sea Star

Sea stars are bottom-dwelling animals with 5–40 arms. A sea star is  capable of regenerating an arm or part of its body. They move slowly over rocks, searching for mussels (clam-like animals that attach themselves to rocks by threads) and other prey. The sea star will use its strong arms to pry open the 2 shells of a mussel. The stomach then everts (comes out of the sea star) and slips between the mussel shells to digest the mussel. When the sea star has com- pleted its meal, the stomach goes back into the sea star.

capable of regenerating an arm or part of its body. They move slowly over rocks, searching for mussels (clam-like animals that attach themselves to rocks by threads) and other prey. The sea star will use its strong arms to pry open the 2 shells of a mussel. The stomach then everts (comes out of the sea star) and slips between the mussel shells to digest the mussel. When the sea star has com- pleted its meal, the stomach goes back into the sea star.

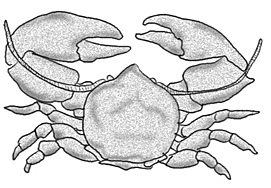

Crab

Crabs are scavengers, feeding at night on dead or decaying animals and plants. They are covered by a hard outer shell called an exo- skeleton. A crab will shed (molt) its exoskeleton many times. After molting, the new shell is soft. This is the only time that the female is able to mate. She carries her eggs under her abdomen until they hatch.

Crabs are scavengers, feeding at night on dead or decaying animals and plants. They are covered by a hard outer shell called an exo- skeleton. A crab will shed (molt) its exoskeleton many times. After molting, the new shell is soft. This is the only time that the female is able to mate. She carries her eggs under her abdomen until they hatch.

Pelagic Ocean Community – The Blue Water Community

The pelagic ocean community is off the continental shelf. This community is often called the blue water community and it extends from the water’s surface to 600 feet deep. The animals in this community have no seaweeds, rocks, or ocean floor to hide in. In order to survive in this community, the animals must have a way to escape predators. Speed is very important in this community. Many fish such as baitfish (herring, anchovy, capelin and other small schooling fish) escape predation by the sheer numbers in their schools.

Critters Found in Pelagic Oceans

Albatross

The great wanderers of the oceans, albatross have long thin wings (up to 10 feet) which they use for gliding. By gliding, albatross can cover long distances without using much energy. This is very important to their survival, since vast areas of the oceans are lacking in sea life. Albatross feed on fish and plankton. They will fly thousands of miles in a year, and may not come to shore for several years. Albatross come to shore only to breed and raise their young. On land they are quite awkward, and islanders that live where there are albatross colonies often call them “goonie birds.”

Flying Fish

The flying fish can glide through the air farther than the distance of 2 football fields. It uses its long wing-like pectoral fins to help it escape its enemies. The lower half of the tail is twice as long as the upper half and helps the fish swim up to 35 miles per hour before lift-off.

The flying fish can glide through the air farther than the distance of 2 football fields. It uses its long wing-like pectoral fins to help it escape its enemies. The lower half of the tail is twice as long as the upper half and helps the fish swim up to 35 miles per hour before lift-off.

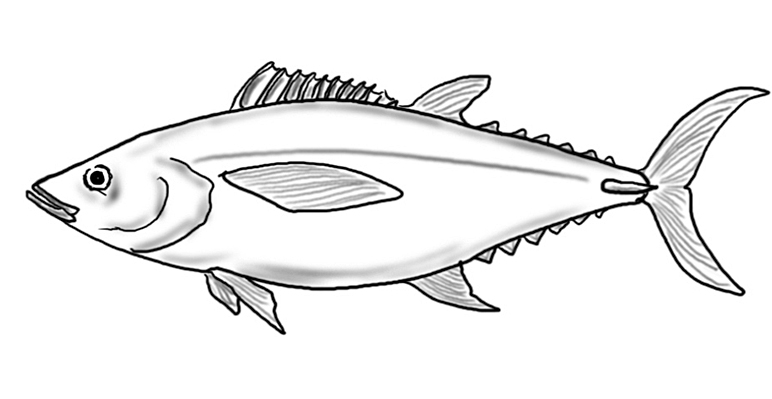

Tuna

Tuna grow to be over 1,000 pounds in weight. The tuna is one of the fastest fish in the world, swimming up to 50 miles per hour. It is a schooling fish and undertakes great migrations, often swimming an entire ocean in a year. Because of its constant motion, the tuna is one of the few fish whose body temperature is higher than the temperature of the water.

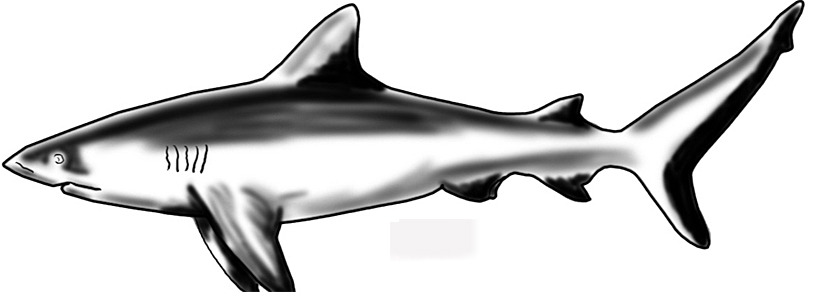

Shark

Shark

Sharks are the tigers of the sea. They are some of the fastest swimmers in the ocean and feed on many kinds of fish, including tuna and marlin. They also eat sea turtles, seals, whales, and dolphins. Sharks are often referred to as “perfect killing machines.” They can detect small quantities of blood in water (the equivalent of 1 drop of blood in 25 gallons of water) at distances greater than a quarter mile. The teeth of sharks are adapted for slicing and are one of the hardest materials produced by an animal. The teeth are loosely set into the jaw of the shark. As a result, a shark will have several rows of replacement teeth in its jaw. In 10 years a shark may lose as many as 20,000 teeth. Sharks have strong jaw muscles, capable of biting with a pressure of 44,000 pounds per square inch (a human bite exerts only 150 pounds per inch). The most feared man-eating shark is the great white shark. The largest great white ever caught was 21 feet long, and weighed over 2 tons.

The Abyss – The Deep-water Community

The abyss community is off the continental shelf in deep water (3,000-10,000 feet deep). This is such a desolate area that you would not expect anything to be living there. The animals in this community never see the sun because it is continually dark. The animals in this community rely upon dead things drifting down from the surface for food. Since there is not much food in the abyss, the fish are small, usually less than a foot in length. The fish are slow moving and they have devised many ingenious ways to capture food. Many of the fish will attempt to eat others larger than themselves. Usually their mouth openings are very large. Many have a series of lights called photophores that attract prey to them.

Critters Found in the Abyss

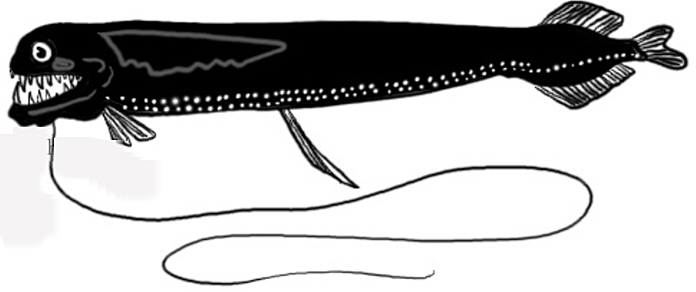

Viperfish

The viperfish is less than 12 inches long and has a large mouth with long, needle-like teeth. Its jaw is very similar to a snake’s, since

it allows the viperfish to swallow things larger than itself. It also has a series of photophores on its side that attract potential prey to it in the darkness.

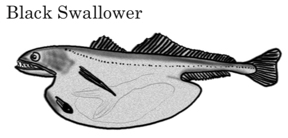

Black Swallower

The black swallower also has photophores along its side, and a mouth that opens wide. Its stomach will expand many times its normal size to hold the large prey that it captures.

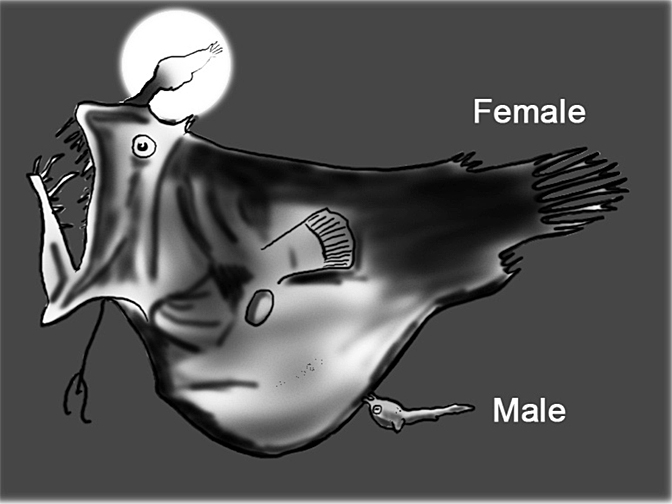

Anglerfish

The top of an anglerfish’s head has a small lure with a light. This is used to attract potential prey. The male anglerfish (1/2 inch) attaches itself to the body of the female (3 inches). Its sole function in life is to fertilize the eggs of the female.

So You Want to Be an Oceanographer

Now you are ready to create something beautiful!

What to do:

1. Download the Creature Page

2. Download pages 1 and 2 of the marine community mural and tape them together or redraw mural pages 1 and 2 on 11 x 17 inch paper.

3. Draw or cut out each creature and put them in the community they are most likely to be found.

4. Write 2-4 words beside each sketch that describes the animal’s special adaptation to its marine community (i.e., “ray – flattened body”).

Creature Page Download Creature Page

Download Creature Page

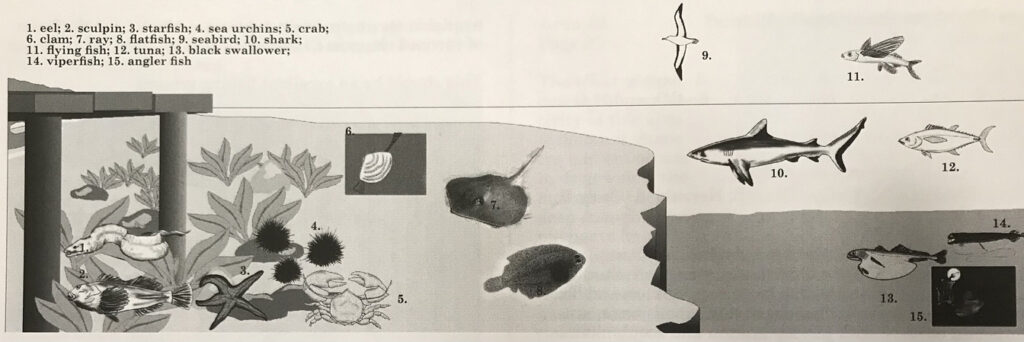

Marine Communities Key

Up Close and Personal with a Famous Oceanographer

Dr. Eugenie Clark, Shark Researcher (The Shark lady)

At what age did you first become interested in the ocean? Was there one special event that led to your decision to work as an oceanographer?

Age 9, on my first visit to an aquarium.

What do you like most about the career that you’ve chosen?

The fact that I can combine two things I love to do the most: diving in the sea and watching fishes and sharks.

What do you like the least about your career?

The paper work that does not concern my research or teaching. The frustration of not being able to answer all of the wonderful letters I receive, especially those from children (she receives over 1,000 letters a year). Note: Dr. Clark would be most likely to answer letters from students who enclose a self-addressed, stamped envelope.

If you were to give a young oceanographer one piece of advice, what would you tell him or her?

Follow your dream. You will work much harder and better at what you love to do and study most. There is a lot of hard work ahead and many courses are required (math, statistics, chemistry, physics, etc.) to become a good biologist. But it is worth it!

What skill or personal attribute helped you to attain your goal?

Writing and speaking.

What are your fears for the great oceans of the planet?

I am optimistic that the present change in attitude of younger people (and the obvious need for global conservation) will turn the tide and save the oceans. Young people understand how important this is now!

What dreams do you have for the next 20 years of your life?

I have now retired from full-time teaching and teach one course a year, leaving me more time to scuba dive and do research. I also want to “play” in my Japanese garden. There is no age limit for scuba diving. I hope to be diving when I’m 90. (As of 2010, Dr. Clark has been diving for 65 years and she is 88 years old.)

[Before this interview Dr. Clark traveled to the Sea of Cortez, near La Paz, Mexico, to dive with whale sharks. She wrote an article for National Geographic (Dec. 1992) on whale sharks. This trip was a continuation of her research.]

I was in the Sea of Cortez two weeks ago. We had 30 whale sharks around our boat. We also saw two gray whales, seven fin whales, two Brydes whales and about 50 manta rays. I have never seen such large numbers of plankton feeders. I could see that there was some kind of upwelling occurring. Nutrient material from the upwelling was available to the plankton, so all of these big plankton feeders were coming in to feed.

What is the secret of your vitality?

I’ve never smoked, I watch my cholesterol intake, and when I’m not scuba diving I try to go to the gym 3 times a week for aerobics. I love my work! I’ve taught over 4,000 students about life in the oceans and I’ve ridden 26 whale sharks (the largest was 55 feet long). Once I slipped in the bathtub and knocked myself out—my most dangerous accident. Imagine the newspaper headlines if I had died: “Shark Lady Dies in Bathtub.”

Describe your work at the Red Sea.