The Short Life of an Early Spring Bee.

The Short Life of an Early Spring Bee.

Look at this barren hillside. Who would guess that beneath the ground is a whole colony of bees awaiting the warmth of the sun, so they can emerge. Known as the cellophane bees, they are the first bees to appear in the spring. Their adult lives are short (one month) and they depend upon the weather to cooperate. Anyone who lives in Minnesota knows that our weather patterns tend to fluctuate (e.g., sunny and warm one day and cold and snowy the next).

This is where Heather Holm picks up the story. Heather is a biologist, as well as a nationally known bee researcher and author. She has studied not only the life cycle of many dozens of bee species, but also the plants they need to pollinate for their survival.

Heather has located and examined the cellophane bee’s nesting areas for the past four years. Below is her video of male cellophane bees patrolling the colony looking for a female to mate with. Most people would run the other way if they saw hundreds of bees buzzing around. But not Heather, for she is what we call an “Earth Guardian,” a person who cares about the small things on our planet.

Cellophane bees remain in their underground homes for eleven months. First as larvae eating the food provided for them by their mother (who died the previous spring). Then in late summer, they pupate (similar to a butterfly) and eventually turn into an adult. If the soil temperature gets above 50°F and it is sunny outside, the adult males will emerge from their underground home for the first time. They will fly around the surface looking for a female to mate with (see Heather’s video above) .

Apparently, the male’s main purpose in life is to mate with a female. Their adult life is very brief (less than a month) and they will die shortly after mating with the female.

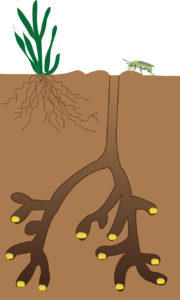

After emerging from the ground and mating with a male, the female begins digging her nest for her larvae. The hole can be up to 10 inches deep, with side branches where she builds oval cells to place the pollen and nectar she collects.

Once she has enough food for her larvae in the cell, the female starts laying eggs at the bottom of her nest and uses the sperm to fertilize those eggs ( they will become females). When there is no more sperm, she lays unfertilized eggs (they become males) closer to the surface. The following spring, the males, who are closer to the surface, dig their way out first and then later the females emerge.

The females have only four weeks to accomplish the following tasks: mate; dig their ground nest, gather pollen from nearby willow or red maple trees; stock the nest with pollen for their larva and lay their eggs.

Minnesota is not an ideal place for cellophane bees to flourish. They can encounter several challenges, such as the changing weather conditions, predators digging out their nests, and humans disturbing their nests. It is a tough life, but many are able to survive. By the first of May, all of the males and most of the females will have completed their life cycle and will die. It is nature’s way.

See Heather’s video of a female cellophane bee gathering pollen and nectar from a red maple tree.

Questions about Cellophane bees

1. Do cellophane bees sting?

The male does not have a stinger, but the female does. Heather walked right in the middle of the colony and they did not react to her. She said the only way someone could be stung is to pick up a female in your hand.

Cellophane-like lining of that protects the larva and its food. Photo courtesy of Max McCarthy and Nick Dorian, bee researchers From MA.

2. How did cellophane bee get their name?

The female lines the nest with a blend of her saliva and a glandular secretion from her abdomen. When these two materials combine, they form a waterproof cellophane-like lining that protects the larva from flooding during heavy rains.

3. In Heather’s video I saw hundreds of bees in one area. Are they like a yellow jacket wasp and have a central nest?

No, each female cellophane bee builds her own nest.

4. Where can I go to see a cellophane bee colony?

Cellophane bees like south facing, flat ground that gets plenty of sunlight. They like the ground to be bare and the soil to be sandy.

Many thanks to Heather Holm for sharing her wisdom with Nature School. To see her website go to: https://www.pollinatorsnativeplants.com/

Thanks to Janine Pung, Kathy Adams and Cindy Eyden for their suggestions on improving the text.

a very informative(as always)article and great videos too. Thank you Larry and Heather for another gem from “The Old Naturalist”!

During our Fool’s Spring a week or so ago on a warm sunny day, my kids and I encountered a large bee on our patio and were very surprised. It seemed so early. We noticed the bee did not have a stinger. Now I am wondering if perhaps it was a male cellophane bee!

Cellophane bees have such cute faces.

Isn’t nature amazing!