Thanks to Amelia Ladd for her beautiful pen and ink sketches.

Time of the Grasshoppers

Bush Katydid

photo by Lawrence Wade

For the past 20 years I have been working with 2nd graders studying grasshoppers. When you spend as much time as I have in the weeds looking for grasshoppers, their uniqueness and beauty goes right to your heart.

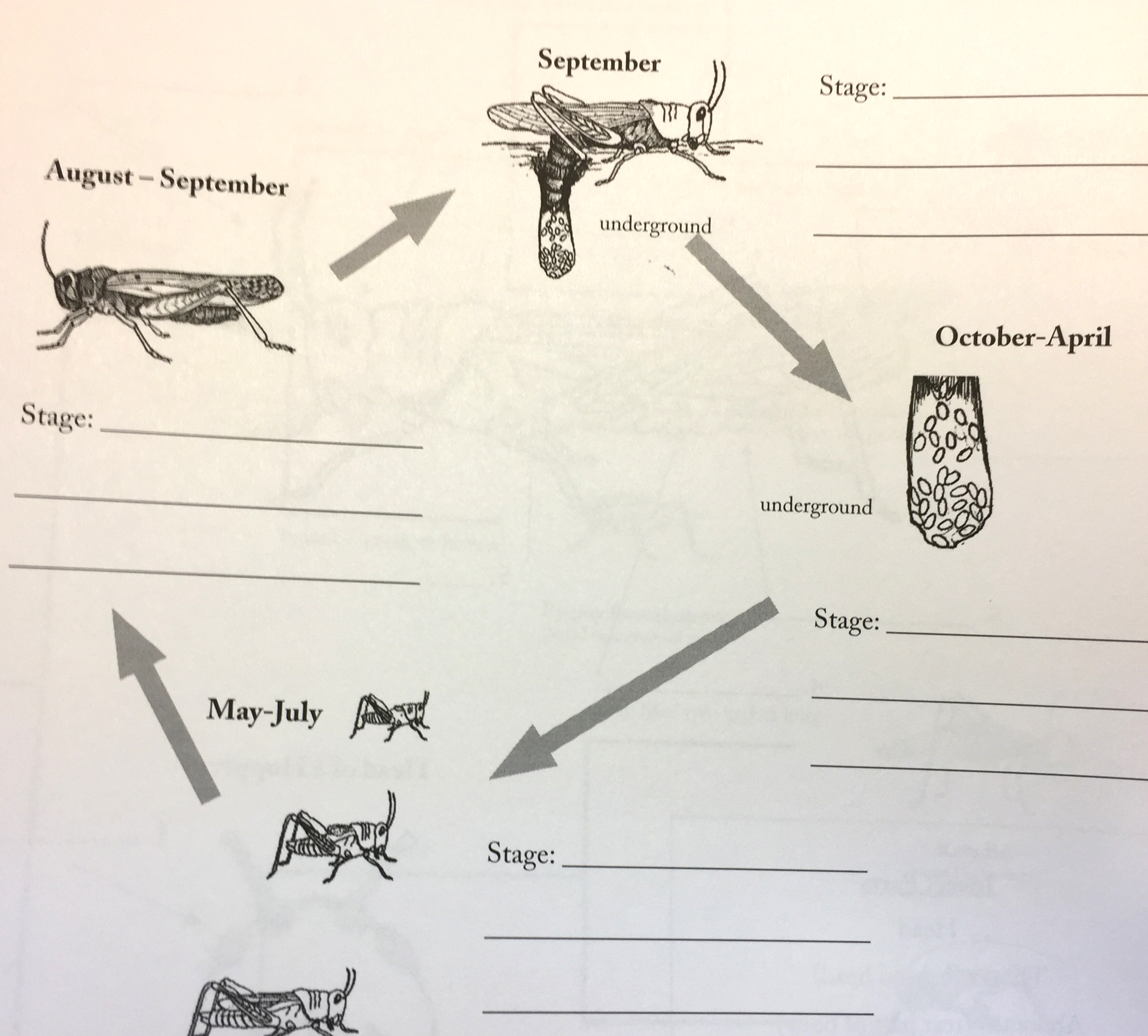

Grasshopper Life Cycle

Nature Seeker Workbook

Late summer/early fall is the Time of the Grasshoppers. In the past month I have noticed that the number of adult grasshoppers/crickets in the neighborhood has increased dramatically. It has taken the whole summer for the hoppers to go through their life cycle and most are now adults. In the spring, the eggs hatch, however, if the rains come before the eggs hatch, many get washed out. The young hoppers go through at least five nymph stages. During this time they cannot fly. The last stage of their lives, they “get their wings” becoming adults, and the singing begins.

Katydid

At the beginning of the post is photo of a katydid. To hear a Katydid calling at night click on the highlighted (Katydid) above.

Snowy Tree Cricket

Songs of Insects

One of my favorites is a night singer that calls from the trees, the snowy tree cricket. It makes a continuous pulse, and is also called the “temperature cricket”, since the pulse changes with the temperature. You can figure out the outside temperature by counting the number of pulses in 15 seconds and multiply by 4, adding 32.

Snowy Tree Cricket calling at night.

The formula to determine the temperature from a snowy tree cricket is as follows:

________________ + _____40_______ = ______________

# of pulses in 15 seconds Temperature in Fahrenheit

Short -horned Grasshopper laying eggs

Nature Seeker Workbook

As soon as a hard frost hits, the “singing” drops from 100% to 0%. It is a shock and difficult to deal with emotionally since it tells us that the seasons are changing. There is also a “quiet beauty” in knowing that the grasshoppers have completed their life cycles. The eggs resting in the ground, promise the continuation their species next year.

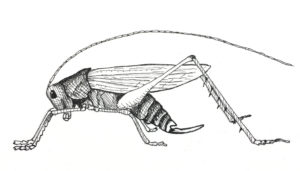

Carolina Grasshopper

Photo by Lawrence Wade

The Carolina grasshopper or locust is normally found on bare ground. It is one of our largest grasshoppers in Minnesota (2-3 inches long). They are easily identified when they fly because they have black wings.

Male Meadow Grasshopper calling from the grassland.

photo by Lawrence Wade

Female Meadow Grasshopper showing her sharp ovipositor at the end of the abdomen.

Nature Seeker Workbook

Meadow grasshoppers are found in tall marsh and prairie grass. The males make a repetitive buzzing sound in the grass during the day. The females are attracted to the sound. After they mate, the female will lay her eggs in a blade of grass using her knife-like ovipositor.

Meadow Grasshoppers calling in the weeds during the day.

Grasshopper Predators

Argiope or Garden Spider

photo by Lawrence Wade

The Argiope spider is a predator on grasshoppers and I often see them in weeds. They make a beautiful web up to 3 feet across. Grasshoppers that fly/jump into the web are quickly wrapped up and mummified by the spider. The female Argiope is 4 times larger than the male.

Leopard frog

Photo by Lawrence Wade

The leopard frog is also a predator on grasshoppers and other grassland insects.

Grasshopper Laboratory

Download the Grasshopper activity pages from Nature Seeker Workbook

Download the Grasshopper activity pages from Nature Seeker Workbook

GrasshopperActivitySheet copy

Reader Bob Bigham added the following comment about grasshoppers:

“While growing up in Pinckneyville , Illinois we would go bug hunting and grasshoppers was one of our favorites. they would “spit tobacco juice” if we held them too tight. One day we flipped one over and it had a bright red hour glass on its belly, just like a black widow.”

Reader Becky Knickerbocker shared the following story:

Yesterday I was sitting outside on the patio at Chapel View Home in Hopkins. I was visiting with a 96 year old blind woman in a wheelchair. The sun was warming us and we were talking about the plants and animals I could see. Birds were singing, bees were buzzing, crickets were chirping, and squirrels and chipmunks were running past us with nuts in their mouths. All of a sudden a grasshopper landed on her knee. She said, “Oh, how fun. I like it. Don’t shoo it away. I can feel it!”

Nice explicit on grasshoppers. I didn’t know about their life cycle. Live and learn. Hope you’re well.

Great article – I knew nothing of the life cycle of grasshoppers. It reminded me of the wonderful sound of the crickets in the evenings when I grew up in Panama. (I just found a recording of crickets online and listened for a moment to bring back the memories even more).

Now is the time of the last butterflies! Here in Stockholm WI, on the east bank of Lake Pepin, clouded sulfurs are still commonly about, though their flight pattern is weak and fluttery. They are unusual among butterflies in living well past their last breeding, but not going anywhere either. Rather than migrate, they just flutter about from fall flower to flower sucking up the last nectar before heavy frosts descend. As if that weren’t enough of a sight in late October, I have spotted at least one rare alba (white) form male among the others. We are also seeing a lot of Milbert’s tortoise shells and an occasional eastern comma; rather than killing them, frost will drive them into hibernating under shelter for the winter.