Early Morning Ice Fog, Minnehaha Creek Photograph by Lawrence Wade

Imbolc, Candlemas or Groundhog’s day has always been one of my favorites because the light returns in the seasonal cycles that earth travels in. It is the hope of springtime and warmth. A time to begin planning and planting and growing things. It is a time of renewal. People, way back before calendars, found ways to celebrate and mark the changes in weather, light and the length of their days that happens because the earth is tilted in it’s rotation around the sun.

Imbolc or Imbolg, also called (Saint) Brigid’s Day, is a Gaelic traditional festival marking the beginning of spring. Most commonly it is held on 1 February, or about halfway between the winter solstice and the spring equinox. In pre-Christian times, it was the festival of light or candlemas. This ancient festival marked the mid point of winter, half way between the winter solstice (shortest day) and the spring equinox. Some people lit candles to scare away evil spirits on the dark winter nights. People believed that Candlemas predicted the weather for the rest of the winter just as, in the United States we have the groundhog that sees it’s shadow.

RMaya Whirry

The Twin Cities has almost 10 hours of sunlight; one hour and 15 minutes more sun than on the winter solstice. By mid February, we will gaining three minutes of sunlight each day. The sun angle is higher, and hope is creeping into the dark places of my soul.

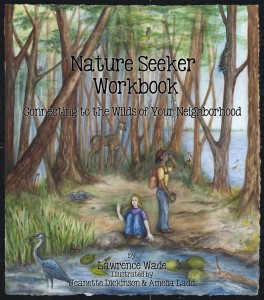

Lawrence Wade

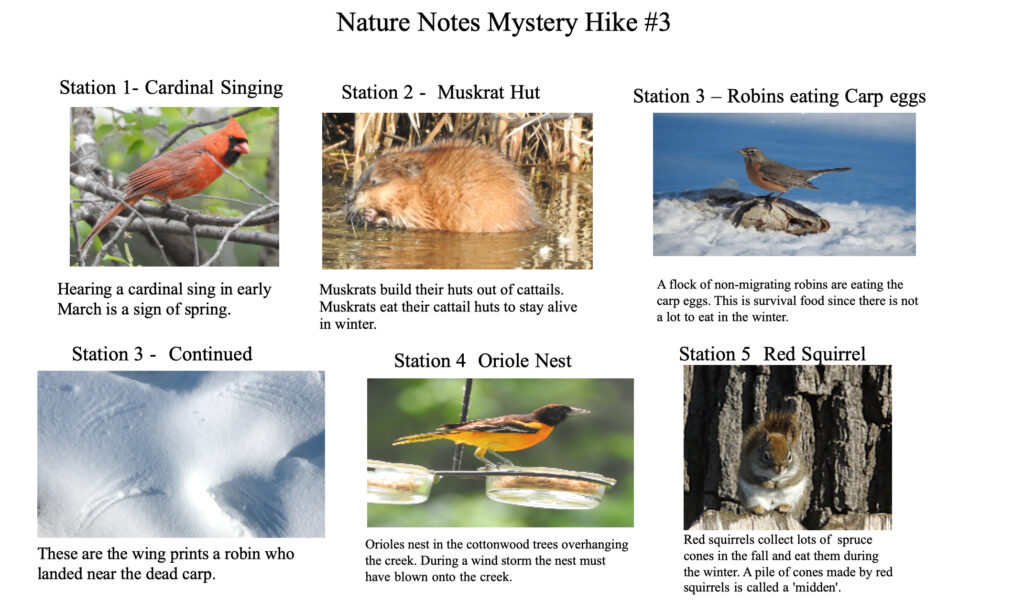

Frozen pieces of art

Photograph by Lawrence Wade

Photograph by Steve Casper

It was a couple of weeks ago during the deep freeze and I had some days to spend with my 14-year-old daughter during holiday break. She said, “How about you help me bake cookies and then we’ll go out walking on Bde Maka Ska (originally named Lake Calhoun).

There we were late in the afternoon, with a temp of 1 degree and windy, walking across Bde Maka Ska, and enjoying every minute. We spent lots of time looking at the depth of the ice, the frozen bubbles, the cracks with new crystals forming, the way the wind forms the snow cover like waves, running and skating across the glare ice; just some great father/daughter time in extreme winter weather. I’m so proud she chose to do that on that particular winter day. And that simple hike with my daughter, who obviously has my love for the great outdoors, was certainly a highlight of my winter.

Steve Casper

Snow Diamonds

Photograph by Linda Jensen

Walking a dog in the suburbs,

with city-ish trappings,

the quiet of snow,

silence of falling flakes.

The fencing of space

but not air.

The snow makes a frosted sculpture

of everything in sight.

A temporary magic

if you are still – long enough to see

the contrast of light and grey,

the white-out that is not white.

It’s peaceful. It’s snow,

crystalized water and light.

Linda Jensen

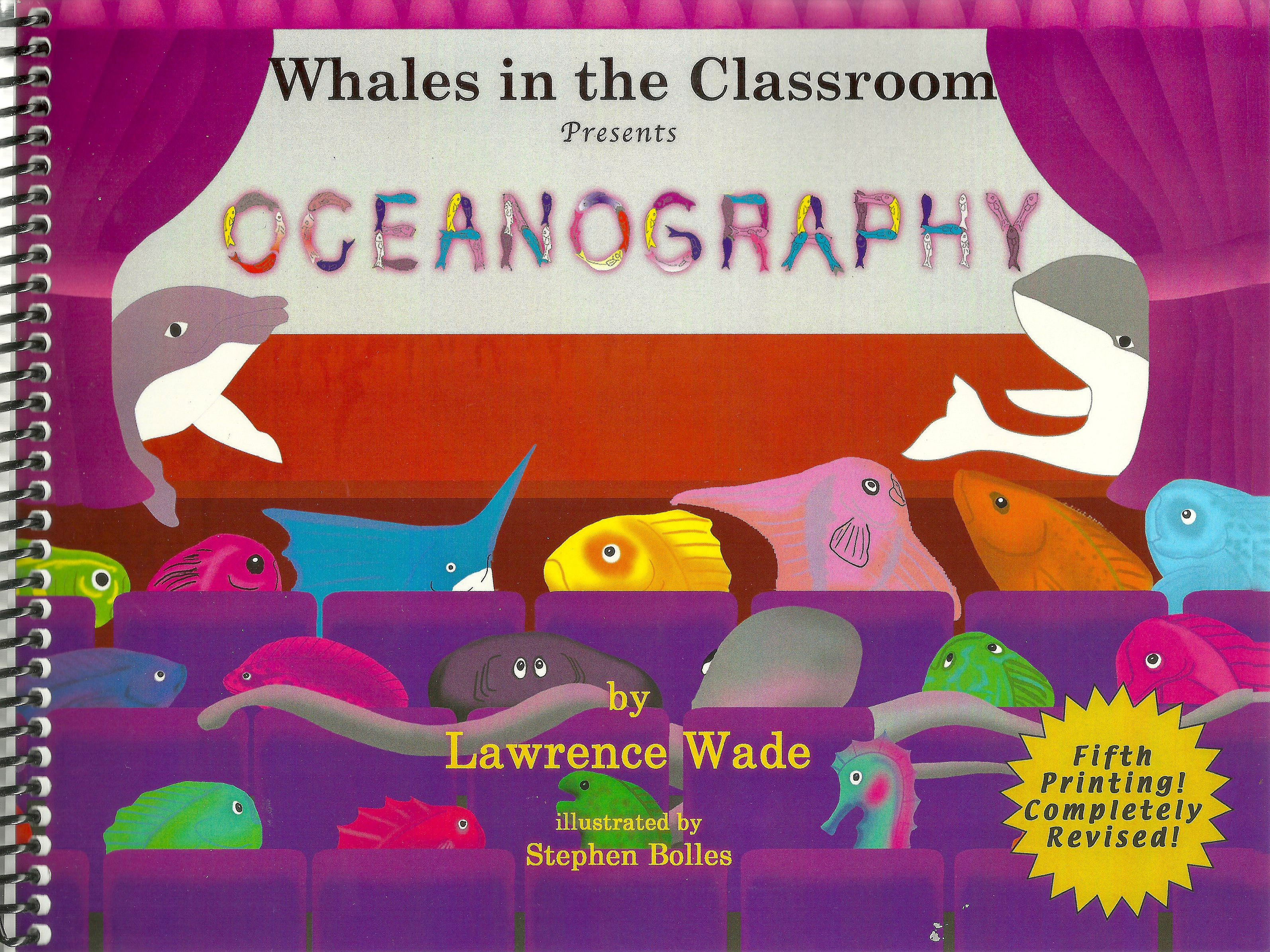

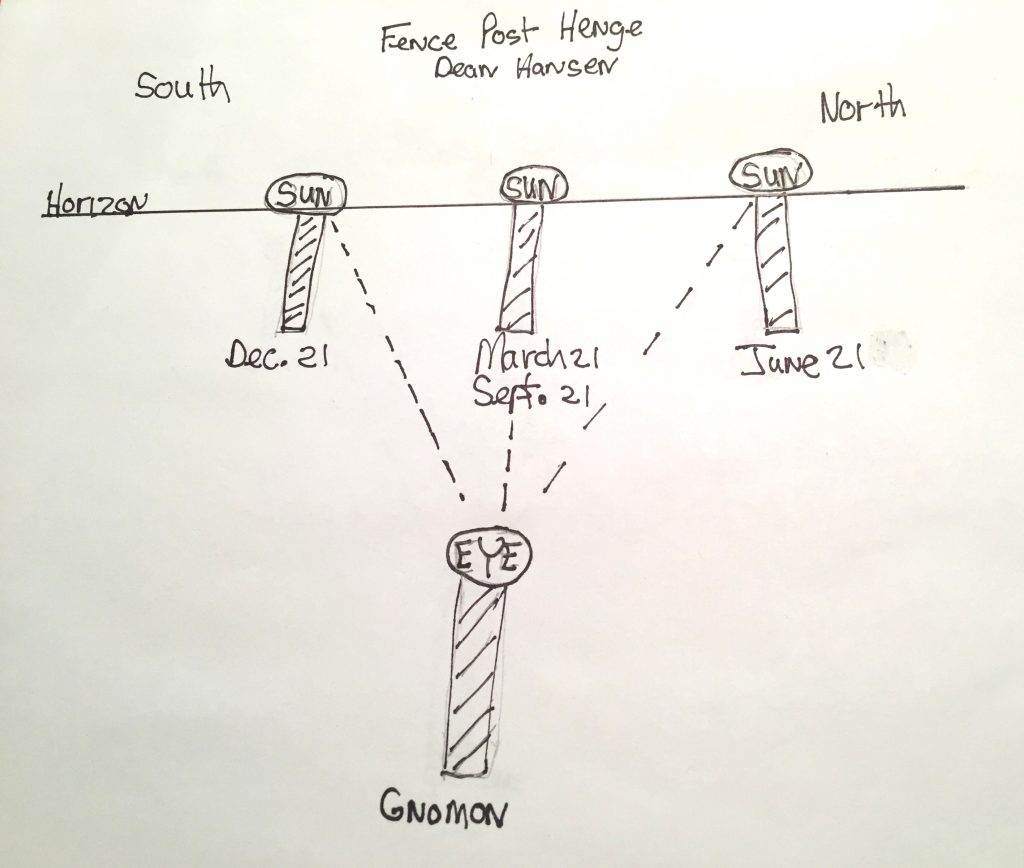

Fence Post Henge – Dean Hansen

I have five acres of land just into WI from where I live in Stillwater, MN. On the top of a hill I have a set of steel fence posts–a standard (gnomon) post and then three posts, each about 30 feet away. I line up the top of the standard post with the top of a post to the SW; the latter is placed so that the setting sun perches on the top of this post as it hits the horizon on Dec. 21, as seen from the top of the gnomon post. Ditto for a post marking where the sun hits the horizon at sunset on March 21 and September 21, and finally for the summer solstice, June 21. Observations are through the filter from an arc welders helmet.

Dean Hansen

The Gnomon post is the foreground. The Winter Solstice post is in background and the top of it lines up with the horizon line. Photograph by Dean Hansen.

Sunset during the Winter Solstice. The Winter Solstice Post is in the foreground. Photo taken through a filter. Photo by Dean Hansen

Horticulture Therapy – Dale Antonson

One of my indoor gardens at the Hopkins Center for the Arts

photo by Dale Antonson

As a lifelong Minnesotan, I have cultivated some ways to keep myself connected with nature year round. I often refer to my hobby as ‘Horticulture Therapy’. I enjoy renewing the soil ‘under my fingernails’ during the winter by caring for plants at the Hopkins Center for the Arts, municipal buildings in Minnetonka and throughout my light filled home. I created an LED light stand with an automatic timer and heating mats for my normally 60℉ basement.

The two shelf basement light stand that I created.

photo by Dale Antonson

I’m able to propagate new plants by taking stem cuttings, including colorful aglaonemas and succulents, nurse back ailing plants and germinate seeds. This is a fun way for me to stay connected to ‘the garden that we live in’, even during the coldest of months.

Dale Antonson

Rooster snow drift

Lawrence Wade

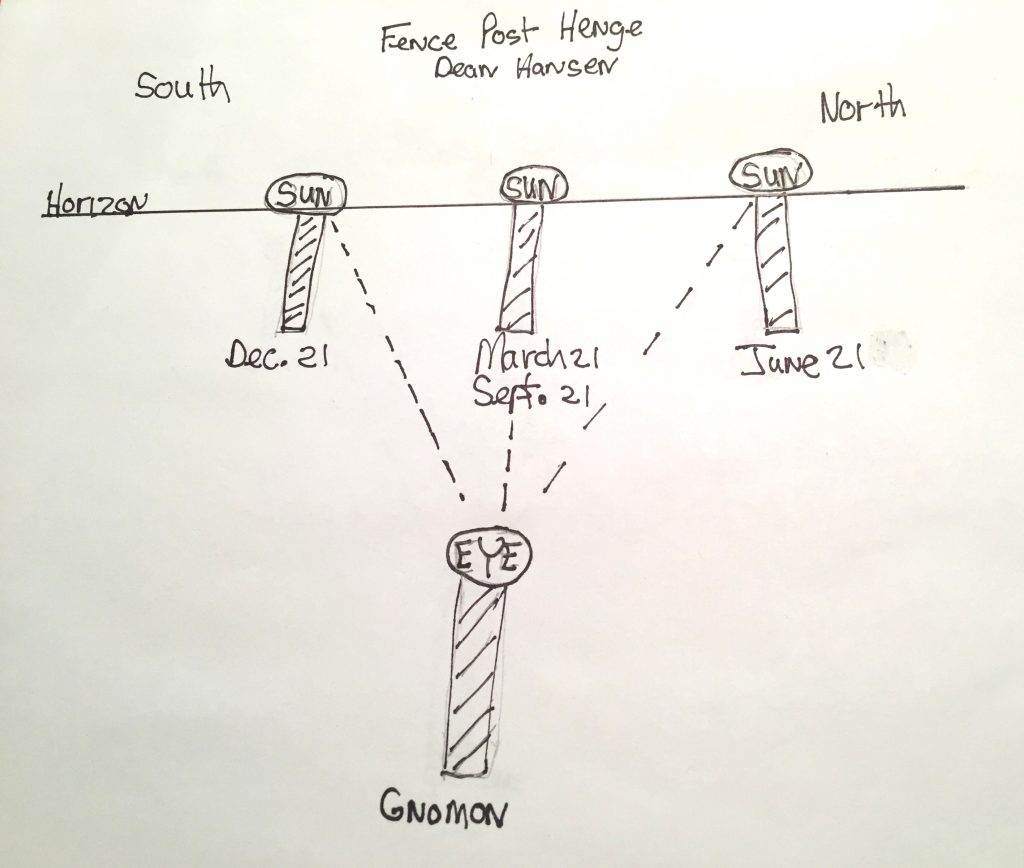

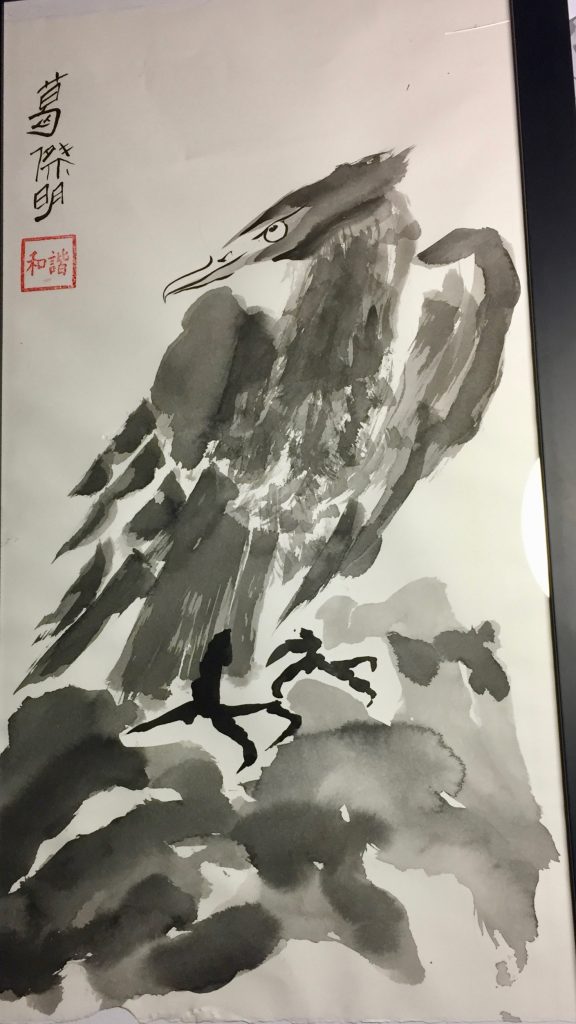

Eagle Visions – Jim Gregory

An Eagle hunting a rabbit on a lake left the evidence in the form of its wings and body. Photograph by Jim Gregory

Eagle Artwork by Jim Gregory

I find the opportunity to express myself about nature through painting to be especially rewarding. When I connect through the artwork, there is a feeling that I am a part of nature and my painting confirms that relationship. It takes courage to face the challenge, but always pays off when I do.

Jim Gregory

Lake Winnebago, WI

Jody Harrell

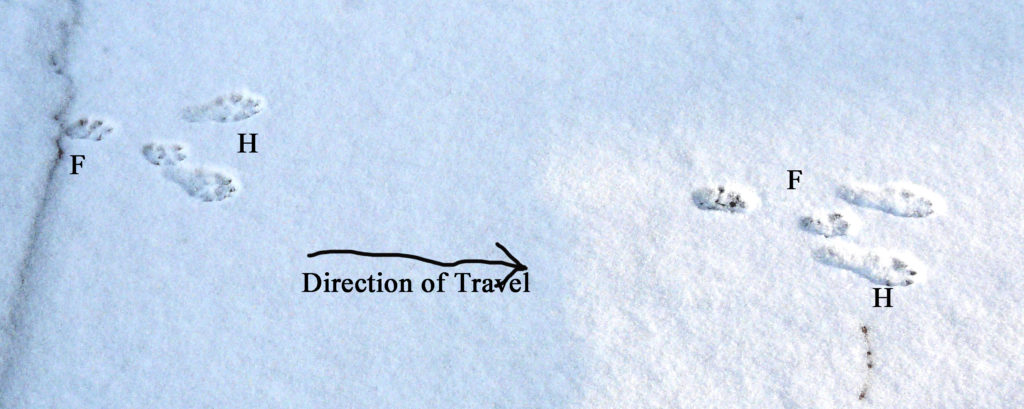

My dog Bravo and I get out twice each day, NO MATTER WHAT! There’s something about the air, the sounds, the lack of other sounds, the light, the snow laden branches, the critter tracks in the snow and the beckoning woods – it makes it all worthwhile for a farm girl at heart and her frisky British Lab.

Gretchen Alford

River Otter plunge hole and slide

Photograph by Lawrence Wade

I have never actually seen a river otter on Minnehaha Creek, but I can feel their presence so deeply, when I see otter slides, plunge holes, scat and chewed up fish heads .

Lawrence Wade

photo by Jody Harrell

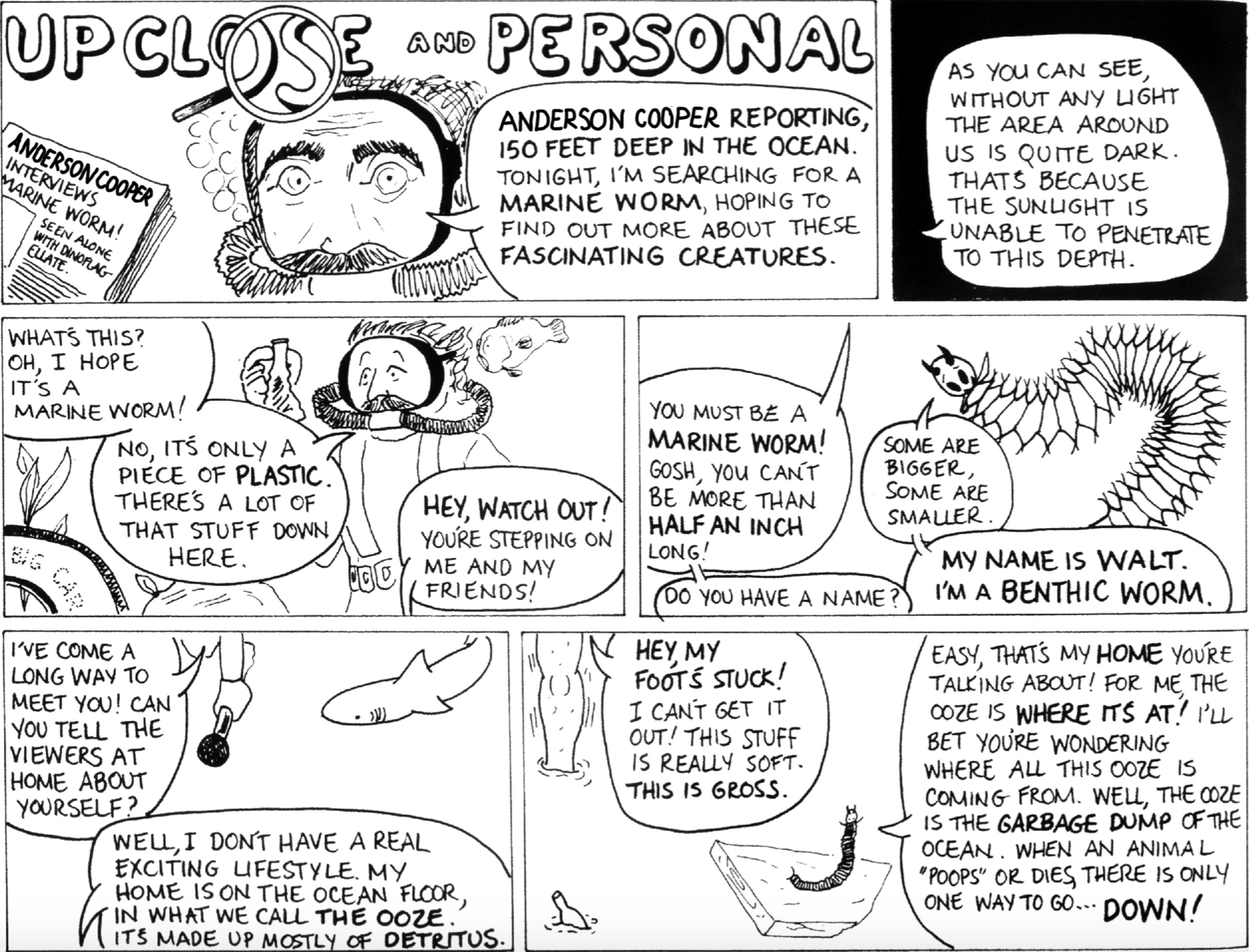

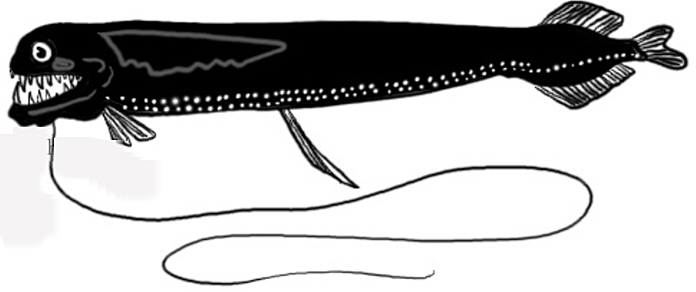

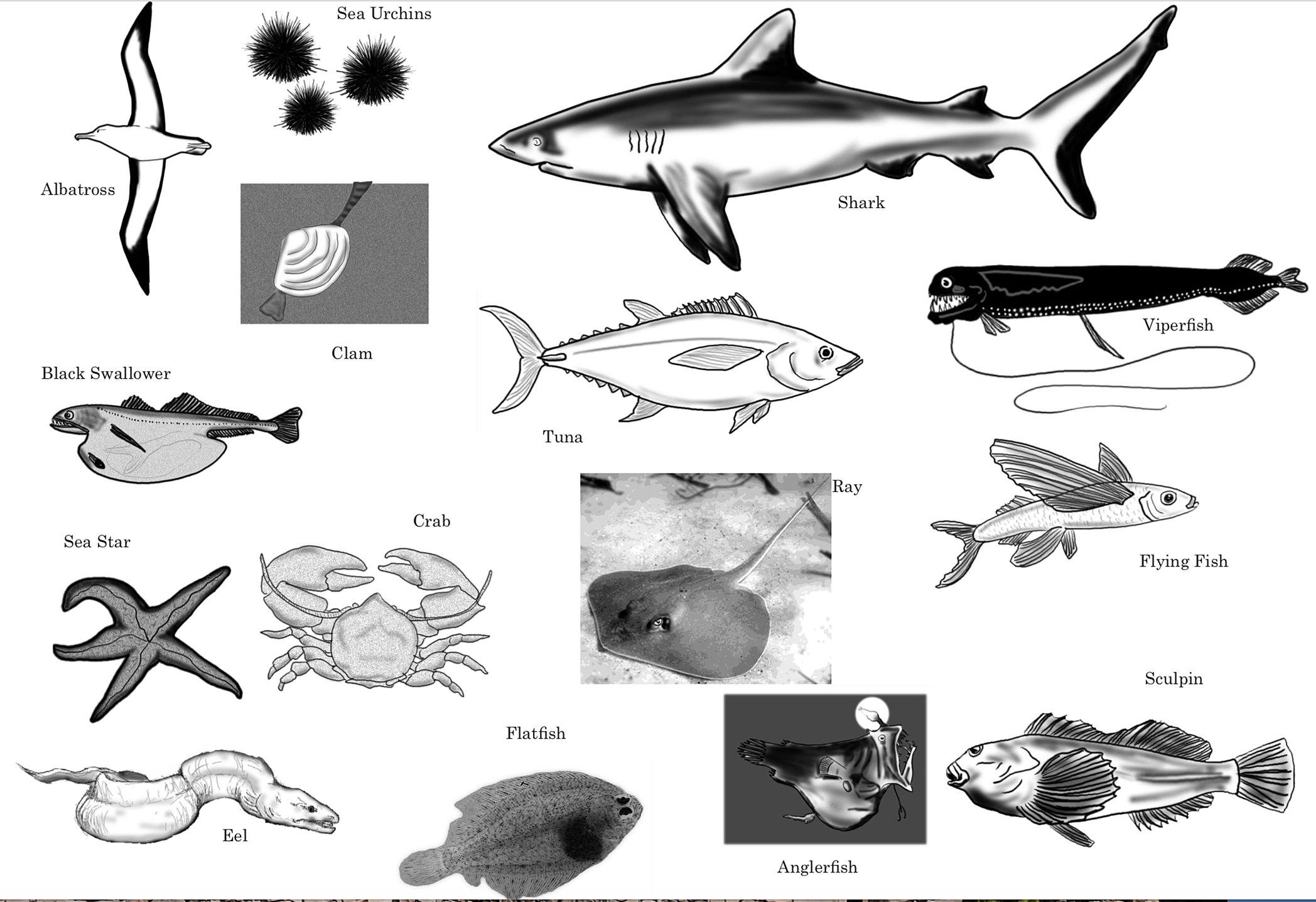

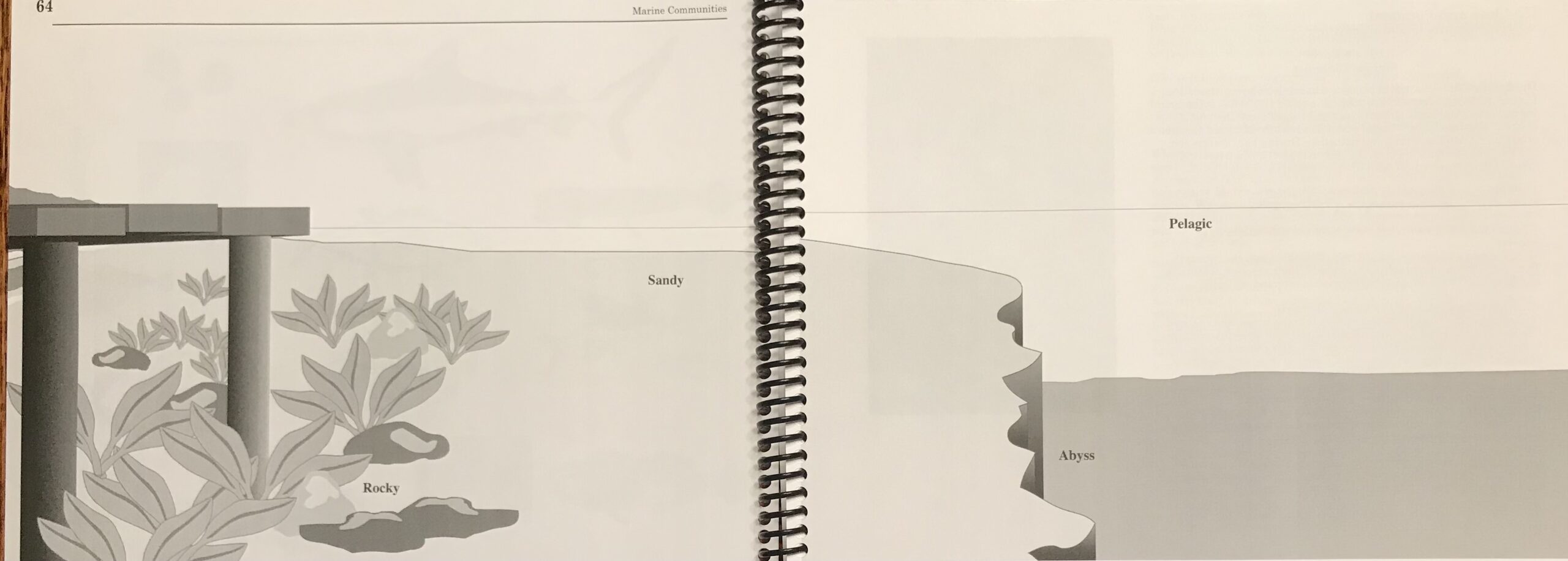

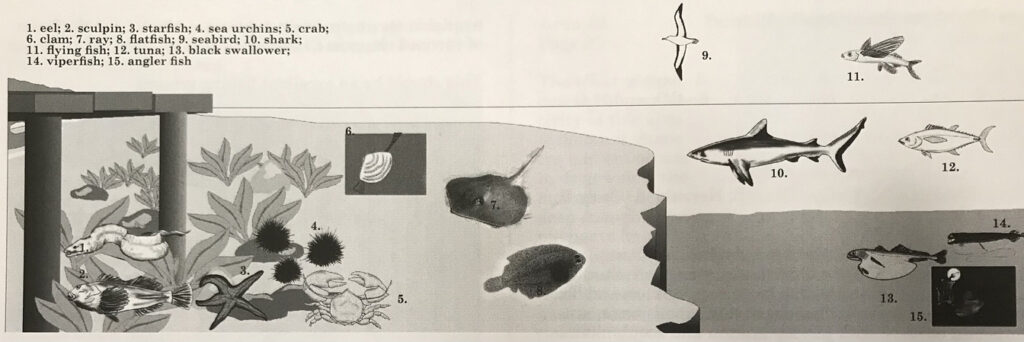

Why are marine worms important?

Why are marine worms important?

Page 42-43

Page 42-43