So much is changing every day here in the North Country. After a winter of white and brown, Nature has burst out in a symphony of colors.

Thanks to all of the contributors who shared their photos and thoughts to this posting including Mary Goehle, Holly Einess, Jeff Saslow, Heather Holm, Sabrina Harvey, and Janine Pung.

Warbler Migration

During the week of May 9th, there was an influx of many different species of warblers. Warblers are extremely beautiful, but difficult to photograph because they are small and always on the move.

Yellow Warbler

Mary Goehle

Maybe the yellow warbler (pictured above) will take up residency here for the summer. I’ll have to listen for its ‘sweet, sweet, sweet, I’m so sweet’ song.

I’m a novice birder and have been enjoying watching warblers flitting about the trees as they pass through on their migration. Mary Goehle

American Redstart

Lawrence Wade

Magnolia Warbler

Mary Goehle

Black and White Warbler

Lawrence Wade

Chesnut-sided Warbler

Lawrence Wade

The Green Tinge

Big Willow Park – Minnetonka, MN

Mary Goehle

I love when the leaves are just starting to come out. They look delicate, almost like lace, especially in the evening sunlight. There are several ironwood trees in this area. They’ve finally given up the marcescent leaves they were holding onto over the winter to make room for the new. Mary Goehle

Tree Flowers

Tree flowers are an important food source for early pollinators.

Willow flowers

Holly Einess

Red Maple Flowers

Holly Einess

Pollinators

Text and photos by Heather Holm. For more info on Heather’s work go to:

https://www.pollinatorsnativeplants.com/about-the-author.html

Two-spotted bumble bee gyne (Bombus bimaculatus) collects pollen from wild plum.

Photo by Heather Holm

New bumble bee queens (gynes), have been emerging the last few weeks from their winter hibernation. Gynes, which later become queens once they establish a nest and produce offspring, are the longest lived caste in the bumble bee colony, surviving for approximately ten to twelve months. Their life begins the previous summer or autumn when they are reared to adulthood by their mother and sisters in a bumble bee colony. Prior to hibernating, the gynes feed on sugar-rich nectars produced by flowering plants, and mate with a male. The calories and nutrients from the consumed nectars are stored in organ-like tissues called fat stores, and the sperm in a separate organ – the spermatheca. While hibernating, they use the energy from the fat stores for nutrients and warmth, and an antifreeze-like substance circulates through their body to prevent them from freezing. The winter hibernation in a shallow burrow in the ground is precarious, and many gynes don’t survive because they do not have enough reserves or fat stores. Those gynes that do survive until spring are famished and need nearby food (flower nectar) to help them prepare for the week-long search to find a place to nest.

Two-spotted bumble bee gyne (Bombus bimaculatus) visits large-flowered bellwort.

Photo by Heather Holm

With over twenty bumble bee species in Minnesota, each have their unique phenology (and emergence time). Usually the first species I observe emerging from hibernation is the two-spotted bumble bee (Bombus bimaculatus). Last week, the two-spotted bumble bee gynes were beginning to collect pollen from plants, an indication that they have successfully established a nest because pollen is the primary food source they provide in the nest to feed their larvae. Other species I’ve seen in the last week include the black and gold bumble bee (Bombus auricomus) and common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens). These gynes were visiting flowering plants to feed on nectar or nest searching. Nest searching gynes fly low to the ground and spend time investigating cavities under logs, in the ground, gaps under leaf litter or debris, or similar sites that may have once hosted a mouse or chipmunk nest. This searching is time consuming and energy intensive, so frequent refueling (nectar) is needed. Once a nest is established, the queen produces multiple broods, beginning with females (workers), followed by males, then ending with the production of gynes. At the end of the summer, the queen will die as will all the workers and males, but her recently-produced daughters (gynes) will mate, then hibernate, and establish their own annual nest the following spring.

Black and gold bumble bee gyne (Bombus auricomus) visits wild plum.

Photo by Heather Holm

Some of the flowering plants gynes were visiting in my neighborhood this week include wild plum (Prunus americana), large-flowered bellwort (Uvularia grandiflora), and common blue violets (Viola sororia). In the next week or so, look for bumble bees visiting prairie smoke (Geum triflorum) dogwood (Cornus spp.), Virginia waterleaf (Hydrophyllum virginianum), and wild geranium (Geranium maculatum).

Common eastern bumble bee gyne (Bombus impatiens) searches for a nesting site under leaf litter.

Photo by Heather Holm

No Mow May

In the upper Midwest, we love our lawns and many strive to grow the ‘perfect lawn’. But many cities have designated this month as ‘No Mow May’ to try to help early pollinators get a foothold during the warm weather. A recent article in Rewilding Magazine, co-authored by Heather Holm, argues that although ‘No Mow May” is well intentioned, it does not meet the complex survival needs of pollinators. To read the article go to:

https://www.rewildingmag.com/no-mow-may-downside/

Dandelions and violets in my lawn

Lawrence Wade

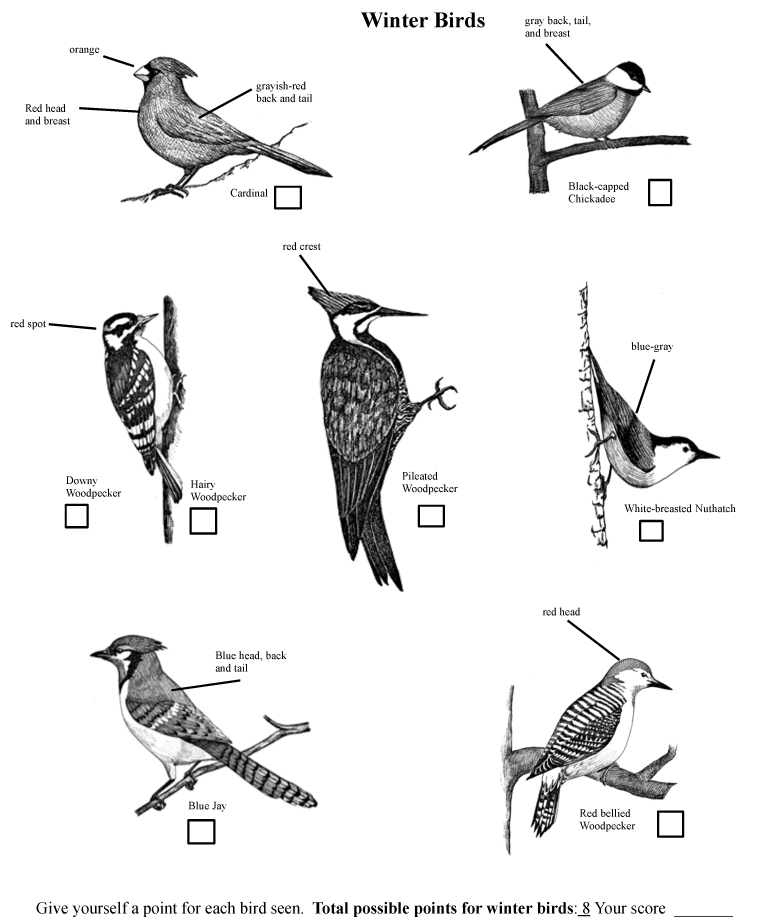

Spring Birds

American Robin and Cedar Waxwing.

Janine Pung

On April 30th, a very large flock of cedar waxwings descended on the crabapple in my front yard. Over the course of several days, I watched them flutter among the branches as they feasted. I saw a pair sweetly pass a berry back and forth, from bill to bill, until one of them swallowed it. I even observed some flying upside down as they tried to land a spot on the crowded tree. Of the many photos I took from my window, this is my favorite…a robin on one branch and a cedar waxwing on another.

Janine Pung

Ruby-Crowned Kinglet in speckled alder

Holly Einess

Great Blue Heron

Holly Einess

Red Wing Blackbird singing “Okalee” from the cattails.

Lawrence Wade

The striking beauty of a female oriole.

Lawrence Wade

Spring Ephemerals

The word ‘ephemeral‘ means ‘to fade quickly‘. ‘Spring ephemerals‘ refers to the wildflowers that are blooming now in our woodlands. Many of the blooms last no more than a week. But, oh, what a week it is….It is healing to feel so much joy at the sight of such beautiful flowers.

Lawrence Wade

Pretty little rue anemone! Prolific this time of year in Big Willow Park.

Mary Goehle

Here’s a lesson in slowing down. It would be easy to miss this bloodroot nestled in among the fungi. It stopped me in my tracks when I spotted it!

Mary Goehle

Showy Trillium

Lawrence Wade

Nodding Trillium – Common in our woodlands

Sabrina Harvey

Wild Ginger. Its red flower hugs the ground so creatures living in the soil can pollinate it.

Lawrence Wade

Jack in the Pulpit

Lawrence Wade

Bellwort

Lawrence Wade

Mayapple

Lawrence Wade

Trout Lily

Holly Einess

Spring Beauty

Holly Einess

Toads and Frogs

American Toad

Jeff Saslow

I slowed down and was made aware of the life in previous passed over places. The waters were teeming with procreation as the humid air held the croaking and calls to mate. The small spaces became everything.

Jeff Saslow, on his experience in toad world.

Chorus Frog Singing

Lawrence Wade

There is nothing better than opening a window at night and being serenaded by the trilling of toads and frogs.

Spending an hour at the edge of a pond listening to the frogs, watching them mate, and fight is like being in a different universe.

Lawrence Wade

The Readers share their experience

From Lizzie Schaeppi: “Our young naturalist out in Woodrill last weekend”.